What is immunity? In medicine, the body's resistance to harmful foreign substances is called "immunity." The human immune system is complex, consisting of immune organs, cells, and molecules. Its primary function is to distinguish between the body's own and foreign components and eliminate them to maintain internal balance. It does not simply eliminate and resist all foreign microorganisms.

Exposure to various pathogens can also strengthen the immune system. The immune system matures with age and exposure to various pathogens. Exposure to pathogens does not necessarily lead to symptoms, because the body's immune system automatically responds to these pathogens, developing immunity to them without symptoms. This process gradually makes the immune system "experienced" and capable of dealing with a variety of pathogens.

Main functions of the immune system:

- Preventing infection: Immediately destroying invading bacteria or viruses.

- Monitoring cancer: Monitoring cell activity throughout the body and immediately destroying abnormal cancer cells.

- Maintaining balance: The immune system, brain, nerves, and endocrine system work together to maintain balance and health.

How does the immune system protect you?

Our body's first line of defense is the skin and mucous membranes, acting like the walls and moat of a kingdom, blocking the invasion of pathogens.

The sebum membrane on the skin's surface is the first barrier, primarily responsible for inhibiting the growth and reproduction of microorganisms. These are the parts of the body most directly exposed to the outside world, guarding the body like a city wall, preventing pathogens from entering. Secretory immunoglobulins (SIgs) on the mucous membranes act as the sharp daggers of the wall, blocking viruses attempting to enter the body.

The second line of defense—the innate immune cells—begins its operations, like patrolling police officers.

Phagocytes constantly patrol the body's various parts, immediately engulfing and dissolving any invaders they detect. Simultaneously, lysozymes and neutrophils in the body's fluids join the fight, helping to eliminate bacteria and viruses.

If the first two lines of defense fail to completely stop the enemy, then our special forces—specific immune systems—must be deployed. This type of immunity is specific, acting only against a particular pathogen or foreign body. For example, a child who has had measles will only develop immunity against the measles virus, but not against other pathogens. Therefore, it is also called specific immunity or acquired immunity.

Specific immunity includes T cells and B cells.

T cells are like special forces soldiers, able to locate and kill viruses in infected cells.

B cells, on the other hand, are like weapons experts, producing antibodies specifically targeting viruses. These antibodies mark viruses, allowing immune cells to quickly target and destroy them in the blood and lymph.

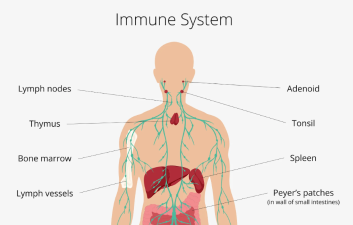

What are the tissues and cells of the immune system?

Immune tissues include bone marrow, thymus, spleen, lymph nodes, tonsils, and intestines.

- Immune cells are divided into: Granular white blood cells, which fight bacteria by engulfing, breaking down, and destroying cells.

- Monocytes: These mature into macrophages, which engulf and break down viruses and cancer cells.

- Lymphocytes: These are divided into three types: T cells (cellular immunity), B cells (humoral immunity), and natural killer cells.

Generally speaking, there are: Killer T cells, which kill both pathogens and cells attacked by pathogens; Helper T cells, which activate macrophages and killer T cells and can also command B cells to produce antibodies; Suppressor T cells, which suppress overactive immune systems to prevent allergies and autoimmune diseases; B cells, which produce antibodies that capture antigens; and Natural Killer cells, which patrol the body 24 hours a day and can individually kill bacteria and cancer cells.